--

[NetZero.com]

[DON'T GET IT TWISTED]NetZero

icq.com

--

LICENSE TO KILL:http://www.euractiv.com/financial-services/eu-pushes-rival-visa-mastercard/article-175506

[THE OMEN]

Base of Operations

Formerly Master of the World's headquarters; (original) unrevealed

First Appearance

(original) Alpha Flight #11 (1983); (Master's) Alpha Flight #110 (1992); (current) Civil War: The Initiative #1 (2007)

Current Members:

Possibly

Arachne (Julia Carpenter),

Sasquatch (Walter Langkowski)

Former Members

Other Members (Honorary, Reserve, etc.)

Omega Flight was organized by

Jerry Jaxon as a counterpart for

Alpha Flight, the team led by his rival,

James Hudson.

Jaxon held Hudson responsible for ruining his career, and he correctly guessed that Hudson had become the hero Guardian. Jaxon shared this information with his new company,

Roxxon Oil, and Roxxon agreed to help Jaxon procure Guardian’s battlesuit, which Jaxon regarded as his own invention.

Guardian confronts Omega Flight

Their help included the use of their robot,

Delphine Courtney. Working together, Jaxon and Courtney formed Omega Flight (

Box (Roger Bochs),

Diamond Lil,

Flashback,

Smart Alec, and

Wild Child), recruiting the team from agents formerly part of the Canadian government's

Department H training grounds for Alpha Flight before the program was shut down.

Omega Flight confronted Alpha Flight at the Edmonton Mall, beginning a protracted battle. Jaxon surprised Guardian by appearing in control of the Box armor, and the two fought single-handedly. Jaxon died when Guardian caused Box to explode, creating a feedback of electricity. Unfortunately, Guardian himself appeared to die after the battle, his battlesuit exploding from irreparable damage.

Delphine Courtney reorganized the Omega Flight, this time wearing a battlesuit similar to Guardian's. Using her disguise to lead Alpha Flight into a trap, Omega Flight was defeated with the help of the mutant

Madison Jeffries, who destroyed Delphine Courtney with the use of his powers to control metal.

Years later, a new Omega Flight was formed, this time under the leadership of the

Master of the World. The Master foresaw an invasion of the alien

Ska’r, He formed the group largely so that he would have ready shock troops at his command. Sure enough, the Ska’r attacked, starting their invasion in Canada. At the same time, the

Magus launched his own

invasion of Earth, using evil doppelgangers of heroes. The Master was content to let the aliens ravage Canada, regarding its casualty an acceptable and unavoidable cost in order to defeat the Magus later. When

Beta Flight appeared to stop the Ska’r, the Master ordered Omega Flight to stop them, and he was eventually forced to involve himself directly as well. Beta Flight, under the direction of

Windshear, was able to rout Omega Flight and the Ska’r, although the Master believed this would only pave the way for the Magus, teleporting himself and the team away.

Months later, the Master launched a plan to usurp control of the Canadian government, using the identity Joshua Lord. When Alpha Flight confronted him, he had not only Omega Flight to protect him but also the Antiguard, a reconditioned

Guardian (James Hudson) that he discovered in a dimension of null space after one of his supposed deaths. The Master rebuilt Hudson's body, brainwashing him into his slave and using him alongside Omega Flight to destroy his enemies. In fact, Omega Flight nearly succeeded in destroying the Alphans, until Hudson's wife and teammate

Vindicator managed to reach her husband and he turned on the Master. The Master disappeared after his defeat, and the final fate of the members of Omega Flight remain unrevealed.

When the

Superhuman Registration Act became law, various villains and unregistered heroes began to cross into the Canada to escape the SRA. This caused a problem for the Canadian government due to Alpha Flight demise.

Iron Man agreed to help the Canadian government by sending a group of registered heroes to Canada.

Sasquatch and

Talisman teamed up with

Arachne,

Guardian (Michael Pointer) (formerly known as the Collective), and

U.S.Agent to form the new Omega Flight in order to fight a horde of demons, a

Tanaraq possessed Sasquatch, and the

Wrecking Crew. They also got assistance from extraterestial known as

Beta Ray Bill who had taken the task of guarding those demons Wrecking Crew freed. During the battle that followed Beta Ray Bill tricked the demon hordes to follow him into a dimensional portal, once inside the portal Guardian destroyed it trapping Beta Ray Bill and the demons in another dimension. For this act of bravery Beta Ray Bill was granted honorary membership on the team. Despite Bill sacraficing himself, Omega Flight still remains together.

More on Marvel.com: http://marvel.com/universe/Omega_Flight#ixzz2P7hEXBcl

http://www.dccomics.com/justiceleague

[CONFEDERATE.COM]

[ICON]

--

[RACE_LOGIC]

[BANG-OLUFSEN.COM]Dino246.com

[MASS CUSTOMIZATION]

OVERLORD_APOCALYPSE

NOW

[SNOWBIRD]|[THE WONDER TWINS] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warlock_(New_Mutants)http://buglabs.net/

IGNITION

[id]=id-mag.com

http://buglabs.net/

CHRYSLER NEW YORKER:= ' http://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=new+york+jay+z+and+alicia+keys&mid=72CA57966298350E781272CA57966298350E7812&view=detail&FORM=VIRE3 '

REEVES CALLWAY CORVETTE:= ' http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:2011_Tom_Hardy_TTSS_Premiere.jpg '

--

http://en.memory-alpha.org/wiki/Locutus_of_Borg

--

HOME PAGE=JamesDean.com

[IT'S MY LIFE]

For Pete's Sake:=' Piero Lardi Ferrari'

I Peter 4:11_"Built It, And They Will Come'

DINO.666 6th Avenue, NY NY

[MOTO GUZZO][RED LINE SNOWMOBILES]

freedom-nation.newsvine.com

[KING JAMES BIBLE]|[MI_BIBELO]

666: June 6, 2006_TheWhiteParty

1.800.800.8900. 1.800.THE.DUNGEON, The DungeonMaster_http://www.sing365.com/music/lyric.nsf/No-Such-Thing-lyrics-John-Mayer/94C72F8E0515775648256BA000312DFE

SISTENE CHAPEL: Story Line

Cell1=The Creation of Adam

Cell1=ArtAnatomy, by William Rimmer

Cell1=TheAwakening.jpg

Hyperlnk_Revelation 1:11

Revelation11:1|DuPont=StewartREEDDesign.com

999: The Deluge=

[MALACHI 1-4]|[EZEKIEL 33][REVELATION 22][16-19]||[EZEKIEL 1:Chariot of Fire][RR][PSALMS 119:33]|[HE=Optiwise4.0]

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0319262/

http://www.vevo.com/watch/rihanna/hard/USUV70904413?source=instantsearch

Piero Lardi Ferrari: Spin Out Ferrari-->Estate of Enzo Anselmo Ferrari

My gift to your family and descendents: Ferrari. LUKE 11: hallowed is thy name_ENZO

Revelation 3:12_DINO

Revelation 3:21_ENZO

[THOMAS PINK]:= ' There You Go '

http://www.vevo.com/watch/rihanna/russian-roulette/USUV70903688?source=instantsearch

P 3/4:=K-11 SuperAmerica

[PATMOS][20]

MINOS OF CRETE:= ' http://www.tumblr.com/dashboard '

--

VWVortex.com:= ' mshf.com '

RISE OF THE SILVER SURFUR:= ' http://www.urmediazone.com/signup?sf=search&ref=4798141&q=SubMariner+%5BComplete%5D '

Unlike at his cathedral, there is no permanent

cathedra for the Pope in St Peter's Basilica, so a removable throne is placed in the Basilica for the Pope's use whenever he presides over a liturgical ceremony. Prior to the liturgical reforms that occurred in the wake of the

Second Vatican Council, a huge removable canopied throne was placed above an equally removable dais in the choir side of the "Altar of the Confession" (the

high altar above the tomb of St Peter and beneath the monumental bronze

baldachin); this throne stood between the apse and the Altar of the Confession.

This practice has fallen out of use with the 1960s and 1970s reform of Papal liturgy and, whenever the Pope celebrates Mass in St. Peter's Basilica, a simpler portable throne is now placed on platform in front of the Altar of the Confession. However, whenever Pope

Benedict XVIcelebrated the

Liturgy of the Hours at St Peter's, a more elaborate removable throne was placed on a dais to the side of the Altar of the Chair. When the Pope celebrates Mass on the Basilica steps facing

St. Peter's Square, portable thrones are also used.

In the past, the pope was also carried on occasions in a portable throne, called the

sedia gestatoria. Originally, the

sedia was used as part of the elaborate procession surrounding papal ceremonies that was believed to be the most direct heir of

pharaonic splendor, and included a pair of

flabella (fans made from ostrich feathers) to either side.

Pope John Paul I at first abandoned the use of these implements, but later in his brief reign began to use the

sedia so that he could be seen more easily by the crowds. However, he did not restore the use of the flabella. The use of the

sedia was abandoned by

Pope John Paul II in favor of the so-called "

popemobile" when outside. Near the end of his pontificate, Pope John Paul II had a specially-constructed throne on wheels that could be used inside.

Prior to 1978, at the

Papal conclave, each

cardinal was seated on a throne in the

Sistine Chapel during the balloting. Each throne had a

canopy over it. After a successful election, once the new pope accepted election and decided by what name he would be known, the cardinals would all lower their canopies, leaving only the canopy over the newly-elected pope. This was the new pope's first throne. This tradition was dramatically portrayed in the 1963 film,

The Shoes of the Fisherman.

[DINO]

Filename: GOD_SPEED|The Pope Mobile_http://www.tuv-sud.com/home_com

Apocalypse_NOW:= ' TheBodyElectric_http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fame_(1980_film)#Music

- Deus caritas est—"God is love". (1 John 4:8)

Charity is held to be the ultimate perfection of the human spirit, because it is said to both glorify and reflect the nature of God. Confusion can arise from the multiple meanings of the English word "love". The love that is caritas is distinguished by its origin, being divinely infused into the soul, and by its residing in the will rather than emotions, regardless of what emotions it stirs up. According to Aquinas, charity is an absolute requirement for happiness, which he holds as man's last goal.

Charity has two parts: love of God and love of man, which includes both love of one's neighbor and one's self.

Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not charity, I am become

as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal. And though I have

the gift of prophecy, and understand all mysteries, and all knowledge; and though I have all faith, so that I could remove mountains, and have not charity, I am nothing. And though I bestow all my goods to feed

the poor, and though I give my body to be burned, and have not charity, it profiteth me nothing.

Charity never faileth: but whether there be prophecies, they shall fail; whether there be tongues, they shall cease; whether there be knowledge, it shall vanish away. For we know in part, and we prophesy in part. But when that which is perfect is come, then that which is in part shall be done away.

When I was a child, I spoke as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things. For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.

And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these

is charity.

Note that the

King James Version uses both the words

charity and

love to translate the idea of

caritas / ἀγάπη: sometimes it uses one, then sometimes the other, for the same concept. Most other English translations, both before and since, do not; instead throughout they use the same more direct English word

love, so that the unity of the teaching should not be in doubt. Love can have other meanings in English, but as used in the

New Testament it almost always refers to the virtue of

caritas.

--

St. Peter's is a church in the Renaissance style located in Rome west of the

River Tiber and near the

Janiculum Hill and

Hadrian's Mausoleum. Its central

dome dominates the skyline of Rome. The basilica is approached via

St. Peter's Square, a forecourt in two sections, both surrounded by tall colonnades. The first space is oval and the second trapezoid. The facade of the basilica, with a

giant order of columns, stretches across the end of the square and is approached by steps on which stand two 5.55 metres (18.2 ft) statues of the 1st century apostles to Rome, Saints

Peter and

Paul.

[7][8]

The basilica is

cruciform in shape, with an elongated nave in the

Latin cross form but the early designs were for a centrally planned structure and this is still in evidence in the architecture. The central space is dominated both externally and internally by one of the largest domes in the world. The entrance is through a

narthex, or entrance hall, which stretches across the building. One of the decorated bronze doors leading from the narthex is the

Holy Door, only opened in

Holy Years.

[7]

The interior is of vast dimensions by comparison with other churches.

[4] One author wrote: "Only gradually does it dawn upon us – as we watch people draw near to this or that monument, strangely they appear to shrink; they are, of course, dwarfed by the scale of everything in the building. This in its turn overwhelms us."

[9]

The apse with St. Peter's Cathedra supported by four Doctors of the Church

The nave which leads to the central dome is in three bays, with piers supporting a barrel-vault, the highest of any church. The nave is framed by wide aisles which have a number of chapels off them. There are also chapels surrounding the dome. Moving around the basilica in a clockwise direction they are: The

Baptistery, the Chapel of the

Presentation of the Virgin, the larger Choir Chapel, the

Clementine Chapel with the altar of

St Gregory, the

Sacristy Entrance, the left

transept with altars to the

Crucifixion of St Peter,

St Joseph and

St Thomas, the altar of the

Sacred Heart, the Chapel of the Madonna of Colonna, the altar of St. Peter and the Paralytic, the apse with St. Peter's

Cathedra, the altar of St. Peter raising Tabitha, the altar of the

Archangel Michael, the altar of the

Navicella, the right transept with altars of

St Erasmus, Saints Processo and Martiniano, and

St Wenceslas, the altar of

St Basil, the Gregorian Chapel with the altar of the Madonna of Succour, the larger Chapel of the

Holy Sacrament, the Chapel of

St Sebastian and the Chapel of the Pietà.

[7] At the heart of the basilica, beneath the high altar, is the

Confessio or

Chapel of the Confession, in reference to the confession of faith by St. Peter, which led to his martyrdom. Two curving marble staircases lead to this underground chapel at the level of the Constantinian church and immediately above the burial place of Saint Peter.

The entire interior of St. Peter's is lavishly decorated with marble, reliefs, architectural sculpture and gilding. The basilica contains a large number of tombs of popes and other notable people, many of which are considered outstanding artworks. There are also a number of sculptures in niches and chapels, including

Michelangelo's

Pietà. The central feature is a

baldachin, or canopy over the Papal Altar, designed by

Gian Lorenzo Bernini. The

sanctuary culminates in a sculptural ensemble, also by Bernini, and containing the symbolic

Chair of Saint Peter.

One observer wrote: "St Peter's Basilica is the reason why Rome is still the center of the civilized world. For religious, historical, and architectural reasons it by itself justifies a journey to Rome, and its interior offers a palimpsest of artistic styles at their best..."

[10]

The American philosopher

Ralph Waldo Emerson described St. Peter's as "an ornament of the earth ... the sublime of the beautiful."

[11]

Panorama of St. Peter's Square

St. Peter's Basilica is one of four

Papal Basilicas or

Major Basilicas of Rome

[12] the others being the

Basilica of St. John Lateran,

Santa Maria Maggiore and

St. Paul outside the Walls. It is the most prominent building in the

Vatican City.

Its dome is a dominant feature of the skyline of Rome. Probably the largest church in

Christendom,

[2] it covers an area of 2.3 hectares (5.7 acres). One of the holiest sites of Christianity in the Catholic Tradition, it is traditionally the burial site of its titular

Saint Peter, who was one of the

twelve apostles of Jesus and, according to Catholic Tradition, also the first

Bishop of Antioch and later first

Bishop of Rome, the first Pope. Although the New Testament does not mention Peter's martyrdom in Rome, Catholic tradition, based on the writings of the

Fathers of the Church,

[clarification needed] holds that his tomb is below the

baldachin and altar; for this reason, many Popes have, from the early years of the Church, been buried there. Construction of the current basilica, over the old Constantinian basilica, began on 18 April 1506. At length on 18 November 1626,

Pope Urban VIII solemnly dedicated the church.

[4]

St. Peter's Basilica is neither the Pope's official seat nor first in rank among the Major Basilicas of Rome. This honour is held by the Pope's cathedral, the

Archbasilica of St. John Lateran which is the

mother church of all churches and parishes in communion with the

Roman Catholic Church. However, St. Peter's is most certainly the Pope's principal church, as most Papal ceremonies take place there due to its size, proximity to the Papal residence, and location within the Vatican City walls. The "

Chair of Saint Peter" or

cathedra, an ancient chair sometimes presumed to have been used by Saint Peter himself, but which was a gift from

Charles the Bald and used by various popes, symbolises the continuing line of

apostolic succession from Saint Peter to the present pope. It occupies an elevated position in the apse, supported symbolically by the

Doctors of the Church, and enlightened symbolically by the

Holy Spirit.

[13]

Saint Peter's burial site

Crepuscular rays are regularly seen in St. Peter's Basilica at certain times each day.

After the

crucifixion of Jesus in the second quarter of the 1st century AD, it is recorded in the Biblical book of the

Acts of the Apostlesthat one of his twelve disciples, Simon known as Saint Peter, a fisherman from

Galilee, took a leadership position among Jesus' followers and was of great importance in the founding of the

Christian Church. The name Peter is "Petrus" in Latin and "Petros" in Greek, deriving from "

petra" which means "stone" or "rock" in

Greek.

It is believed by a long tradition that Peter, after a ministry of about thirty years, travelled to Rome and met his

martyrdom there in the year 64 AD during the reign of the

Roman Emperor Nero. His execution was one of the many martyrdoms of Christians following the

Great Fire of Rome. According to

Origen, Peter was crucified head downwards, by his own request because he considered himself unworthy to die in the same manner as Jesus.

[14] The crucifixion took place near an ancient Egyptian obelisk in the

Circus of Nero.

[15]The obelisk now stands in

Saint Peter's Square and is revered as a "witness" to Peter's death. It is one of several ancient

Obelisks of Rome.

[16]

According to tradition, Peter's remains were buried just outside the Circus, on the

Mons Vaticanus across the

Via Cornelia from the Circus, less than 150 metres (490 ft) from his place of death. The Via Cornelia (which may have been known by another name to the ancient Romans) was a road which ran east-to-west along the north wall of the Circus on land now covered by the southern portions of the Basilica and Saint Peter's Square. Peter's grave was initially marked simply by a red rock, symbolic of his name.

[citation needed] A shrine was built on this site some years later. Almost three hundred years later,

Old St. Peter's Basilica was constructed over this site.

[15]

In 1939, in the reign of Pope Pius XII, 10 years of archaeological research began, under the crypt of the basilica, an area inaccessible since the 9th century. Indeed, the area now covered by the

Vatican City had been a cemetery for some years before the Circus of Nero was built. It was a burial ground for the numerous executions in the Circus and contained many Christian burials, perhaps because for many years after the burial of

Saint Peter many Christians chose to be buried near him. The excavations revealed the remains of shrines of different periods at different levels, from Clement VIII (1594) to

Callixtus II (1123) and

Gregory I (590–604), built over an

aedicula containing fragments of bones that were folded in a tissue with gold decorations, tinted with the precious

murex purple. Although it could not be determined with certainty that the bones were those of Peter, the rare vestments suggested a burial of great importance. On 23 December 1950, in his pre-Christmas radio broadcast to the world,

Pope Pius XII announced the discovery of

Saint Peter's tomb.

[17]

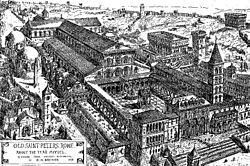

[edit]Old St. Peter's Basilica

Old St. Peter's Basilica was the fourth-century church begun by the

Emperor Constantine between 319 and 333 AD.

[18] It was of typical basilical

Latin Cross form with an apsidal end at the chancel, a wide nave and two aisles on either side. It was over 103.6 metres (340 ft) long, and the entrance was preceded by a large colonnaded

atrium. This church had been built over the small shrine believed to mark the burial place of St. Peter. It contained a very large number of burials and memorials, including those of most of the popes from St. Peter to the 15th century. Like all of the earliest churches in Rome, both this church and its successor had the entrance to the east and the apse at the west end of the building.

[19] Since the construction of the current basilica, the name

Old St. Peter's Basilica has been used for its predecessor to distinguish the two buildings.

[20]

[edit]The plan to rebuild

By the end of the 15th century, having been neglected during the period of the

Avignon Papacy, the old basilica was in bad repair. It appears that the first pope to consider rebuilding, or at least making radical changes was

Pope Nicholas V (1447–55). He commissioned work on the old building from

Leone Battista Alberti and

Bernardo Rossellino and also got Rossellino to design a plan for an entirely new basilica, or an extreme modification of the old. His reign was frustrated by political problems and when he died, little had been achieved.

[15] He had, however, ordered the demolition of the

Colosseum and by the time of his death, 2,522 cartloads of stone had been transported for use in the new building.

[15][21]

Pope Julius II planned far more for St Peter's than Nicholas V's program of repair or modification. Julius was at that time planning his own tomb, which was to be designed and adorned with sculpture by

Michelangelo and placed within St Peter's.

[22] In 1505 Julius made a decision to demolish the ancient basilica and replace it with a monumental structure to house his enormous tomb and "aggrandize himself in the popular imagination".

[6] A competition was held, and a number of the designs have survived at the

Uffizi Gallery. A succession of popes and architects followed in the next 120 years, their combined efforts resulting in the present building. The scheme begun by Julius II continued through the reigns of

Leo X (1513–1521),

Hadrian VI (1522–1523).

Clement VII (1523–1534),

Paul III (1534–1549),

Julius III (1550–1555),

Marcellus II (1555),

Paul IV (1555–1559),

Pius IV(1559–1565),

Pius V (saint) (1565–1572),

Gregory XIII (1572–1585),

Sixtus V (1585–1590),

Urban VII (1590),

Gregory XIV (1590–1591),

Innocent IX (1591),

Clement VIII (1592–1605),

Leo XI (1605),

Paul V (1605–1621),

Gregory XV (1621–1623),

Urban VIII (1623–1644) and

Innocent X (1644–1655).

[edit]Financing with indulgences

A German

Augustinian priest,

Martin Luther, wrote to Archbishop Albrecht arguing against this "selling of indulgences". He also included his "Disputation of Martin Luther on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences", which came to be known as

The 95 Theses.

[24] This became a factor in starting the

Reformation, the birth of Protestantism.

[edit]Architecture

[edit]Successive plans

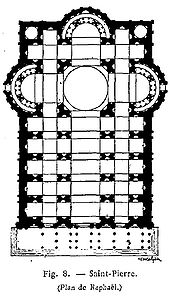

Michelangelo's plan, extended with Maderno's nave and facade

Pope Julius' scheme for the grandest building in Christendom

[6] was the subject of a competition for which a number of entries remain intact in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. It was the design of

Donato Bramante that was selected, and for which the foundation stone was laid in 1506. This plan was in the form of an enormous

Greek Cross with a dome inspired by that of the huge circular Roman temple, the

Pantheon.

[6] The main difference between Bramante's design and that of the Pantheon is that where the dome of the Pantheon is supported by a continuous wall, that of the new basilica was to be supported only on four large piers. This feature was maintained in the ultimate design. Bramante's dome was to be surmounted by a

lantern with its own small dome but otherwise very similar in form to the Early Renaissance lantern of

Florence Cathedraldesigned for Brunelleschi's dome by

Michelozzo.

[25]

Bramante had envisioned that the central dome be surrounded by four lower domes at the diagonal axes. The equal chancel, nave and transept arms were each to be of two bays ending in an apse. At each corner of the building was to stand a tower, so that the overall plan was square, with the apses projecting at the cardinal points. Each apse had two large radial buttresses, which squared off its semi-circular shape.

[26]

When Pope Julius died in 1513, Bramante was replaced with

Giuliano da Sangallo,

Fra Giocondo and

Raphael. Sangallo and Fra Giocondo both died in 1515, Bramante himself having died the previous year. The main change in Raphael's plan is the nave of five bays, with a row of complex apsidal chapels off the aisles on either side. Raphael's plan for the chancel and transepts made the squareness of the exterior walls more definite by reducing the size of the towers, and the semi-circular apses more clearly defined by encircling each with an ambulatory.

[27]

In 1520 Raphael also died, aged 37, and his successor

Baldassare Peruzzi maintained changes that Raphael had proposed to the internal arrangement of the three main apses, but otherwise reverted to the Greek Cross plan and other features of Bramante.

[28] This plan did not go ahead because of various difficulties of both church and state. In 1527 Rome was sacked and plundered by

Emperor Charles V. Peruzzi died in 1536 without his plan being realized.

[6]

At this point

Antonio da Sangallo the Younger submitted a plan which combines features of Peruzzi, Raphael and Bramante in its design and extends the building into a short nave with a wide façade and portico of dynamic projection. His proposal for the dome was much more elaborate of both structure and decoration than that of Bramante and included ribs on the exterior. Like Bramante, Sangallo proposed that the dome be surmounted by a lantern which he redesigned to a larger and much more elaborate form.

[29] Sangallo's main practical contribution was to strengthen Bramante's piers which had begun to crack.

[15]

On 1 January 1547 in the reign of Pope Paul III, Michelangelo, then in his seventies, succeeded Sangallo the Younger as "Capomaestro", the superintendent of the building program at St Peter's.

[30] He is to be regarded as the principal designer of a large part of the building as it stands today, and as bringing the construction to a point where it could be carried through. He did not take on the job with pleasure; it was forced upon him by Pope Paul, frustrated at the death of his chosen candidate,

Giulio Romano and the refusal of

Jacopo Sansovino to leave Venice. Michelangelo wrote "I undertake this only for the love of God and in honour of the Apostle." He insisted that he should be given a free hand to achieve the ultimate aim by whatever means he saw fit.

[15]

[edit]Michelangelo's contribution

Michelangelo took over a building site at which four piers, enormous beyond any constructed since ancient Roman times, were rising behind the remaining nave of the old basilica. He also inherited the numerous schemes designed and redesigned by some of the greatest architectural and engineering minds of the 16th century. There were certain common elements in these schemes. They all called for a dome to equal that engineered by

Brunelleschi a century earlier and which has since dominated the skyline of Renaissance Florence, and they all called for a strongly symmetrical plan of either Greek Cross form, like the iconic

St. Mark's Basilica in Venice, or of a Latin Cross with the transepts of identical form to the chancel, as at

Florence Cathedral.

Even though the work had progressed only a little in 40 years, Michelangelo did not simply dismiss the ideas of the previous architects. He drew on them in developing a grand vision. Above all, Michelangelo recognized the essential quality of Bramante's original design. He reverted to the Greek Cross and, as Helen Gardner expresses it: "Without destroying the centralising features of Bramante's plan, Michelangelo, with a few strokes of the pen converted its snowflake complexity into massive, cohesive unity."

[31]

As it stands today, St. Peter's has been extended with a nave by

Carlo Maderno. It is the chancel end (the ecclesiastical "Eastern end") with its huge centrally placed dome that is the work of Michelangelo. Because of its location within the

Vatican State and because the projection of the nave screens the dome from sight when the building is approached from the square in front of it, the work of Michelangelo is best appreciated from a distance. What becomes apparent is that the architect has greatly reduced the clearly defined geometric forms of Bramante's plan of a square with square projections, and also of Raphael's plan of a square with semi-circular projections.

[32] Michelangelo has blurred the definition of the geometry by making the external masonry of massive proportions and filling in every corner with a small vestry or stairwell. The effect created is of a continuous wall-surface that is folded or fractured at different angles, but lacks the right-angles which usually define change of direction at the corners of a building. This exterior is surrounded by a

giant order of Corinthian pilasters all set at slightly different angles to each other, in keeping with the ever-changing angles of the wall's surface. Above them the huge cornice ripples in a continuous band, giving the appearance of keeping the whole building in a state of compression.

[33]

[edit]Dome – successive and final designs

The dome of St. Peter's rises to a total height of 136.57 metres (448.1 ft) from the floor of the basilica to the top of the external cross. It is the tallest dome in the world.

[34] Its internal diameter is 41.47 metres (136.1 ft), slightly smaller than two of the three other huge domes that preceded it, those of the

Pantheon of

Ancient Rome, 43.3 metres (142 ft), and

Florence Cathedral of the

Early Renaissance, 44 metres (144 ft). It has a greater diameter by approximately 30 feet (9.1 m) than Constantinople's

Hagia Sophia church, completed in 537. It was to the domes of the Pantheon and Florence duomo that the architects of St. Peter's looked for solutions as to how to go about building what was conceived, from the outset, as the greatest dome of Christendom.

[edit]Bramante and Sangallo, 1506 and 1513

The dome of the

Pantheon stands on a circular wall with no entrances or windows except a single door. The whole building is as high as it is wide. Its dome is constructed in a single shell of concrete, made light by the inclusion of a large amount of the volcanic stones tuff and pumice. The inner surface of the dome is deeply

coffered which has the effect of creating both vertical and horizontal ribs, while lightening the overall load. At the summit is an ocular opening 8 metres (26 ft) across which provides light to the interior.

[6]

Bramante's plan for the dome of St. Peter's (1506) follows that of the Pantheon very closely, and like that of the Pantheon, was designed to be constructed in tufa concrete for which he had rediscovered a formula. With the exception of the lantern that surmounts it, the profile is very similar, except that in this case the supporting wall becomes a

drum raised high above ground level on four massive piers. The solid wall, as used at the Pantheon, is lightened at St. Peter's by Bramante piercing it with windows and encircling it with a

peristyle.

In the case of

Florence Cathedral, the desired visual appearance of the pointed dome existed for many years before

Brunelleschimade its construction feasible.

[35] Its double-shell construction of bricks locked together in herringbone pattern (re-introduced from Byzantine architecture), and the gentle upward slope of its eight stone ribs made it possible for the construction to take place without the massive wooden formwork necessary to construct hemispherical arches. While its appearance, with the exception of the details of the lantern, is entirely Gothic, its engineering was highly innovative, and the product of a mind that had studied the huge vaults and remaining dome of Ancient Rome.

[25]

Sangallo's plan (1513), of which a large wooden model still exists, looks to both these predecessors. He realised the value of both the coffering at the Pantheon and the outer stone ribs at Florence Cathedral. He strengthened and extended the peristyle of Bramante into a series of arched and ordered openings around the base, with a second such arcade set back in a tier above the first. In his hands, the rather delicate form of the lantern, based closely on that in Florence, became a massive structure, surrounded by a projecting base, a peristyle and surmounted by a spire of conic form.

[29] According to James Lees-Milne the design was "too eclectic, too pernickety and too tasteless to have been a success".

[15]

[edit]Michelangelo and Giacomo della Porta, 1547 and 1585

St. Peter's Basilica from

Castel Sant'Angeloshowing the dome rising behind Maderno's facade.

Michelangelo redesigned the dome in 1547, taking into account all that had gone before. His dome, like that of

Florence, is constructed of two shells of brick, the outer one having 16 stone ribs, twice the number at Florence but far fewer than in Sangallo's design. As with the designs of Bramante and Sangallo, the dome is raised from the piers on a drum. The encircling peristyle of Bramante and the arcade of Sangallo are reduced to 16 pairs of Corinthian columns, each of 15 metres (49 ft) high which stand proud of the building, connected by an arch. Visually they appear to buttress each of the ribs, but structurally they are probably quite redundant. The reason for this is that the dome is ovoid in shape, rising steeply as does the dome of Florence Cathedral, and therefore exerting less outward thrust than does a hemispherical dome, such as that of the Pantheon, which, although it is not buttressed, is countered by the downward thrust of heavy masonry which extends above the circling wall.

[6][15]

The ovoid profile of the dome has been the subject of much speculation and scholarship over the past century. Michelangelo died in 1564, leaving the drum of the dome complete, and Bramante's piers much bulkier than originally designed, each 18 metres (59 ft) across. Following his death, the work continued under his assistant

Jacopo Barozzi da Vignola with

Giorgio Vasari appointed by Pope Pius V as a watchdog to make sure that Michelangelo's plans were carried out exactly. Despite Vignola's knowledge of Michelangelo's intentions, little happened in this period. In 1585 the energetic Pope Sixtus appointed

Giacomo della Porta who was to be assisted by

Domenico Fontana. The five year reign of Sixtus was to see the building advance at a great rate.

[15]

The engraving by Stefan du Pérac was published in 1569, five years after the death of Michelangelo

Michelangelo left a few drawings, including an early drawing of the dome, and some drawings of details. There were also detailed engravings published in 1569 by Stefan du Pérac who claimed that they were the master's final solution. Michelangelo, like Sangallo before him, also left a large wooden model. Giacomo della Porta subsequently altered this model in several ways, in keeping with changes that he made to the design. Most of these changes were of a cosmetic nature, such as the adding of lion's masks over the swags on the drum in honour of Pope Sixtus and adding a circlet of finials around the spire at the top of the lantern, as proposed by Sangallo. The major change that was made to the model, either by della Porta, or Michelangelo himself before his death, was to raise the outer dome higher above the inner one.

[15]

A drawing by Michelangelo indicates that his early intentions were towards an ovoid dome, rather than a hemispherical one.

[31] In an engraving in

Galasso Alghisi' treatise (1563), the dome may be represented as ovoid, but the perspective is ambiguous.

[36]Stefan du Pérac's engraving (1569) shows a hemispherical dome, but this was perhaps an inaccuracy of the engraver. The profile of the wooden model is more ovoid than that of the engravings, but less so than the finished product. It has been suggested that Michelangelo on his death bed reverted to the more pointed shape. However Lees-Milne cites Giacomo della Porta as taking full responsibility for the change and as indicating to Pope Sixtus that Michelangelo was lacking in the scientific understanding of which he himself was capable.

[15]

Helen Gardner suggests that Michelangelo made the change to the hemispherical dome of lower profile in order to establish a balance between the dynamic vertical elements of the encircling giant order of pilasters and a more static and reposeful dome. Gardner also comments "The sculpturing of architecture [by Michelangelo]... here extends itself up from the ground through the attic stories and moves on into the drum and dome, the whole building being pulled together into a unity from base to summit."

[31]

It is this sense of the building being sculptured, unified and "pulled together" by the encircling band of the deep cornice that led Eneide Mignacca to conclude that the ovoid profile, seen now in the end product, was an essential part of Michelangelo's first (and last) concept. The sculptor/architect has, figuratively speaking, taken all the previous designs in hand and compressed their contours as if the building were a lump of clay. The dome

must appear to thrust upwards because of the apparent pressure created by flattening the building's angles and restraining its projections.

[33] If this explanation is the correct one, then the profile of the dome is not merely a structural solution, as perceived by Giacomo della Porta; it is part of the integrated design solution that is about visual tension and compression. In one sense, Michelangelo's dome may appear to look backward to the Gothic profile of Florence Cathedral and ignore the

Classicism of the Renaissance, but on the other hand, perhaps more than any other building of the 16th century, it prefigures the architecture of the

Baroque.

[33]

[edit]Completion

The dome was brought to completion by Giacomo della Porta and Fontana.

Giacomo della Porta and Fontana brought the dome to completion in 1590, the last year of the reign of

Sixtus V. His successor,

Gregory XIV, saw Fontana complete the lantern and had an inscription to the honour of Sixtus V placed around its inner opening. The next pope,

Clement VIII, had the cross raised into place, an event which took all day, and was accompanied by the ringing of the bells of all the city's churches. In the arms of the cross are set two lead caskets, one containing a fragment of the

True Cross and a relic of

St. Andrew and the other containing medallions of the Holy Lamb.

[15]

In the mid-18th century, cracks appeared in the dome, so four iron chains were installed between the two shells to bind it, like the rings that keep a barrel from bursting. As many as ten chains have been installed at various times, the earliest possibly planned by Michelangelo himself as a precaution, as Brunelleschi did at Florence Cathedral.

Around the inside of the dome is written, in letters 2 metres (6.6 ft) high:

TV ES PETRVS ET SVPER HANC PETRAM AEDIFICABO ECCLESIAM MEAM. TIBI DABO CLAVES REGNI CAELORVM

(

...you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church. ... I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven... Vulgate,

Matthew 16:18–19.)

Beneath the lantern is the inscription:

S. PETRI GLORIAE SIXTVS PP. V. A. M. D. XC. PONTIF. V.

(To the glory of St Peter; Sixtus V, pope, in the year 1590 and the fifth year of his pontificate.)

[edit]Discovery of Michelangelo draft

On 7 December 2007, a fragment of a red chalk drawing of a section of the dome of Saint Peter's, almost certainly by the hand of

Michelangelo was discovered in the Vatican archives.

[37] The drawing shows a small precisely drafted section of the plan of the entabulature above two of the radial columns of the cupola drum. Michelangelo is known to have destroyed thousands of his drawings before his death.

[38] The rare survival of this example is probably due to its fragmentary state and the fact that detailed mathematical calculations had been made over the top of the drawing.

[37]

The nave looking towards the entrance

[edit]The change of plan

On 18 February 1606, under Pope Paul V, the dismantling of the remaining parts of the Constantinian basilica began.

[15] The marble cross that had been set at the top of the pediment by Pope Sylvester and the Emperor Constantine was lowered to the ground. The timbers were salvaged for the roof of the Borghese Palace and two rare black marble columns, the largest of their kind, were carefully stored and later used in the narthex. The tombs of various popes were opened, treasures removed and plans made for reinterment in the new basilica.

[15]

The Pope had appointed

Carlo Maderno in 1602. He was a nephew of

Domenico Fontana and had demonstrated himself as a dynamic architect. Maderno's idea was to ring Michelangelo's building with chapels, but the Pope was hesitant about deviating from the master's plan, even though he had been dead for forty years. The

Fabbrica or building committee, a group drawn from various nationalities and generally despised by the

Curia who viewed the basilica as belonging to Rome rather than Christendom, were in a quandary as to how the building should proceed. One of the matters that influenced their thinking was the Counter-Reformation which increasingly associated a Greek Cross plan with paganism and saw the Latin Cross as truly symbolic of Christianity.

[15]

Another influence on the thinking of both the Fabbrica and the Curia was a certain guilt at the demolition of the ancient building. The ground on which it and its various associated chapels, vestries and sacristies had stood for so long was hallowed. The only solution was to build a nave that encompassed the whole space. In 1607 a committee of ten architects was called together, and a decision was made to extend Michelangelo's building into a nave. Maderno's plans for both the nave and the façade were accepted. The building began on 7 May 1607, and proceeded at a great rate, with an army of 700 labourers being employed. The following year, the façade was begun, in December 1614 the final touches were added to the stucco decoration of the vault and early in 1615 the partition wall between the two sections was pulled down. All the rubble was carted away, and the nave was ready for use by

Palm Sunday.

[15]

Maderno’s façade, with the statues of Sts Peter (left) & Paul (right) flanking the entrance stairs

[edit]Maderno's façade

The façade designed by Maderno, is 114.69 metres (376.3 ft) wide and 45.55 metres (149.4 ft) high and is built of

travertine stone, with a giant order of Corinthian columns and a central pediment rising in front of a tall

attic surmounted by thirteen statues: Christ flanked by eleven of the

Apostles (except Peter, whose statue is left of the stairs) and

John the Baptist.

[39] The inscription below the

cornice on the 1 metre (3.3 ft) tall

frieze reads:

IN HONOREM PRINCIPIS APOST PAVLVS V BVRGHESIVS ROMANVS PONT MAX AN MDCXII PONT VII

(

In honour of the Prince of Apostles, Paul V Borghese, a Roman, Supreme Pontiff, in the year 1612, the seventh of his pontificate)

The façade is often cited as the least satisfactory part of the design of St. Peter's. The reasons for this, according to James Lees-Milne, are that it was not given enough consideration by the Pope and committee because of the desire to get the building completed quickly, coupled with the fact that Maderno was hesitant to deviate from the pattern set by Michelangelo at the other end of the building. Lees-Milne describes the problems of the façade as being too broad for its height, too cramped in its details and too heavy in the attic storey. The breadth is caused by modifying the plan to have towers on either side. These towers were never executed above the line of the facade because it was discovered that the ground was not sufficiently stable to bear the weight. One effect of the façade and lengthened nave is to screen the view of the dome, so that the building, from the front, has no vertical feature, except from a distance.

[15]

[edit]Narthex and portals

Behind the façade of St. Peter's stretches a long portico or "narthex" such as was occasionally found in Italian Romanesque churches. This is the part of Maderno's design with which he was most satisfied. Its long barrel vault is decorated with ornate stucco and gilt, and successfully illuminated by small windows between pendentives, while the ornate marble floor is beamed with light reflected in from the piazza. At each end of the narthex is a theatrical space framed by ionic columns and within each is set a statue, an equestrian figure of

Charlemagne by

Cornacchini(18th century) in the south end and

Emperor Constantine by Bernini (1670) in the north end.

Five portals, of which three are framed by huge salvaged antique columns, lead into the basilica. The central portal has a bronze door created by

Antonio Averulino in 1455 for the old basilica and somewhat enlarged to fit the new space.

[edit]Maderno's nave

Maderno's nave, looking towards the chancel

To the single bay of

Michelangelo's Greek Cross, Maderno added a further three bays. He made the dimensions slightly different to Michelangelo's bay, thus defining where the two architectural works meet. Maderno also tilted the axis of the nave slightly. This was not by accident, as suggested by his critics. An ancient Egyptian obelisk had been erected in the square outside, but had not been quite aligned with Michelangelo's building, so Maderno compensated, in order that it should, at least, align with the Basilica's facade.

[15]

The nave has huge paired pilasters, in keeping with Michelangelo's work. The size of the interior is so "stupendously large" that it is hard to get a sense of scale within the building.

[15][40] The four cherubs who flutter against the first piers of the nave, carrying between them two Holy Water basins, appear of quite normal cherubic size, until approached. Then it becomes apparent that each one is over 2 metres high and that real children cannot reach the basins unless they scramble up the marble draperies. The aisles each have two smaller chapels and a larger rectangular chapel, the Chapel of the Sacrament and the Choir Chapel. These are lavishly decorated with marble, stucco, gilt, sculpture and mosaic. Remarkably, there are very few paintings, although some, such as Raphael's "Sistine Madonna" have been reproduced in mosaic. The most precious painting is a small icon of the Madonna, removed from the old basilica.

[15]

Maderno's last work at St. Peter's was to design a crypt-like space or "Confessio" under the dome, where the Cardinals and other privileged persons could descend in order to be nearer the burial place of the apostle. Its marble steps are remnants of the old basilica and around its balustrade are 95 bronze lamps.

[edit]Influence on church architecture

The design of St. Peter's Basilica, and in particular its dome, has greatly influenced

church architecture in

Western Christendom. Within Rome, the huge domed church of

Sant'Andrea della Valle was designed by Giacomo della Porta before the completion of St Peter's, and subsequently worked on by Carlo Maderno. This was followed by the domes of

San Carlo ai Catinari,

Sant'Agnese in Agone and many others.

Christopher Wren's dome at

St Paul's Cathedral in London, the domes of

Karlskirche in Vienna,

St Nicholas Church, Prague and the

Pantheon, Paris all pay homage to St Peter's. The 19th and early 20th century architectural revivals brought about the building of a great number of churches that imitate elements of St Peter's to a greater or lesser degree, including

St. Mary of the Angels in Chicago,

St. Josaphat's Basilica in

Milwaukee,

Immaculate Heart of Mary in Pittsburgh and

Mary, Queen of the World Cathedral in

Montreal, which replicates many aspects of St Peter's on a smaller scale.

Post-Modernism has seen free adaptations of St Peter's in the

Basilica of Our Lady of Licheń, and the

Basilica of Our Lady of Peace of Yamoussoukro.

[edit]Bernini's furnishings

View of the interior shows the transept arms to right and left, and the chancel beyond the baldacchino.

[edit]Pope Urban VIII and Bernini

As a young boy

Gianlorenzo Bernini (1598–1680) visited St. Peter's with the painter

Annibale Carracci and stated his wish to build "a mighty throne for the apostle". His wish came true. As a young man, in 1626, he received the patronage of

Pope Urban VIII and worked on the embellishment of the Basilica for 50 years. Appointed as Maderno's successor in 1629, he was to become regarded as the greatest architect and sculptor of the

Baroque period. Bernini's works at St. Peter's include the baldacchino, the Chapel of the Sacrament, the plan for the niches and loggias in the piers of the dome and the chair of St. Peter.

[15][31]

[edit]Baldacchino and niches

Bernini's first work at St. Peter's was to design the

baldacchino, a pavilion-like structure 30 metres (98 ft) tall and claimed to be the largest piece of bronze in the world, which stands beneath the dome and above the altar. Its design is based on the

ciborium, of which there are many in the churches of Rome, serving to create a sort of holy space above and around the table on which the Sacrament is laid for the

Eucharist and emphasizing the significance of this ritual. These

ciboria are generally of white marble, with inlaid coloured stone. Bernini's concept was for something very different. He took his inspiration in part from the

baldachin or canopy carried above the head of the pope in processions, and in part from eight ancient columns that had formed part of a screen in the old basilica. Their twisted

barley-sugar shape had a special significance as they were modelled on those of the Temple of Jerusalem and donated by the Emperor Constantine. Based on these columns, Bernini created four huge columns of bronze, twisted and decorated with olive leaves and bees, which were the emblem of Pope Urban.

The altar with Bernini's baldacchino

The baldacchino is surmounted not with an architectural pediment, like most baldacchini, but with curved Baroque brackets supporting a draped canopy, like the brocade canopies carried in processions above precious iconic images. In this case, the draped canopy is of bronze, and all the details, including the olive leaves, bees, and the portrait heads of Urban's niece in childbirth and her newborn son, are picked out in gold leaf. The baldacchino stands as a vast free-standing sculptural object, central to and framed by the largest space within the building. It is so large that the visual effect is to create a link between the enormous dome which appears to float above it, and the congregation at floor level of the basilica. It is penetrated visually from every direction, and is visually linked to the

Cathedra Petri in the apse behind it and to the four piers containing large statues that are at each diagonal.

[15][31]

As part of the scheme for the central space of the church, Bernini had the huge piers, begun by Bramante and completed by Michelangelo, hollowed out into niches, and had staircases made inside them, leading to four balconies. There was much dismay from those who thought that the dome might fall, but it did not. On the balconies Bernini created showcases, framed by the eight ancient twisted columns, to display the four most precious relics of the basilica: the spear of Longinus, said to have pierced the side of Christ, the veil of Veronica, with the miraculous image of the face of Christ, a fragment of the

True Cross discovered in Jerusalem by Constantine's mother, Helena, and a relic of St. Andrew, the brother of St. Peter. In each of the niches that surround the central space of the basilica was placed a huge statue of the saint associated with the relic above. Only St. Longinus is the work of Bernini.

[15] (See below)

Bernini's "Cathedra Petri" and "Gloria"

[edit]Cathedra Petri and Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament

Bernini then turned his attention to another precious relic, the so-called

Cathedra Petri or "throne of St. Peter" a chair which was often claimed to have been used by the apostle, but appears to date from the 12th century. As the chair itself was fast deteriorating and was no longer serviceable, Pope Alexander VII determined to enshrine it in suitable splendour as the object upon which the line of successors to Peter was based. Bernini created a large bronze throne in which it was housed, raised high on four looping supports held effortlessly by massive bronze statues of four

Doctors of the Church, Saints

Ambrose and

Augustine representing the Latin Church and

Athanasius and

John Chrysostom, the Greek Church. The four figures are dynamic with sweeping robes and expressions of adoration and ecstasy. Behind and above the Cathedra, a blaze of light comes in through a window of yellow alabaster, illuminating, at its centre, the Dove of the Holy Spirit. The elderly painter,

Andrea Sacchi, had urged Bernini to make the figures large, so that they would be seen well from the central portal of the nave. The chair was enshrined in its new home with great celebration of 16 January 1666.

[15][31]

Bernini's final work for St. Peter's, undertaken in 1676, was the decoration of the Chapel of the Sacrament.

[41] To hold the sacramental Host, he designed a miniature version in gilt bronze of Bramante's

Tempietto, the little chapel that marks the place of the death of St. Peter. On either side is an angel, one gazing in rapt adoration and the other looking towards the viewer in welcome. Bernini died in 1680 in his 82nd year.

[15]

[edit]St. Peter's Piazza

Two fountains form the axis of the piazza.

To the east of the basilica is the

Piazza di San Pietro, (

St. Peter's Square). The present arrangement, constructed between 1656 and 1667, is the

Baroque inspiration of Bernini who inherited a location already occupied by an Egyptian

obelisk of the 13th century BC, which was centrally placed, (with some contrivance) to Maderno's facade. The obelisk, known as "The Witness", at 25.5 metres (84 ft) and a total height, including base and the cross on top, of 40 metres (130 ft), is the second largest standing obelisk, and the only one to remain standing since its removal from Egypt and re-erection at the

Circus of Nero in 37 AD, where it is thought to have stood witness to the crucifixion of St Peter.

[42] Its removal to its present location by order of

Pope Sixtus V and engineered by

Domenico Fontana on 28 September 1586, was an operation fraught with difficulties and nearly ending in disaster when the ropes holding the obelisk began to smoke from the friction. Fortunately this problem was noticed by a sailor, and for his swift intervention, his village was granted the privilege of providing the palms that are used at the basilica each

Palm Sunday.

[15]

The other object in the old square with which Bernini had to contend was a large fountain designed by Maderno in 1613 and set to one side of the obelisk, making a line parallel with the façade. Bernini's plan uses this horizontal axis as a major feature of his unique, spatially dynamic and highly symbolic design. The most obvious solutions were either a rectangular piazza of vast proportions so that the obelisk stood centrally and the fountain (and a matching companion) could be included, or a trapezoid piazza which fanned out from the façade of the basilica like that in front of the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena. The problems of the square plan are that the necessary width to include the fountain would entail the demolition of numerous buildings, including some of the Vatican, and would minimise the effect of the facade. The trapezoid plan, on the other hand, would maximise the apparent width of the façade, which was already perceived as a fault of the design.

[31]

View of Rome from the Dome of St. Peter's Basilica

Bernini's ingenious solution was to create a piazza in two sections. That part which is nearest the basilica is trapezoid, but rather than fanning out from the façade, it narrows. This gives the effect of countering the visual perspective. It means that from the second part of the piazza, the building looks nearer than it is, the breadth of the façade is minimized and its height appears greater in proportion to its width. The second section of the piazza is a huge elliptical circus which gently slopes downwards to the obelisk at its centre. The two distinct areas are framed by a colonnade formed by doubled pairs of columns supporting an entabulature of the simple

Tuscan Order.

The part of the colonnade that is around the ellipse does not entirely encircle it, but reaches out in two arcs, symbolic of the arms of "the Roman Catholic Church reaching out to welcome its communicants".

[31] The obelisk and Maderno's fountain mark the widest axis of the ellipse. Bernini balanced the scheme with another fountain in 1675. The approach to the square used to be through a jumble of old buildings, which added an element of surprise to the vista that opened up upon passing through the colonnade. Nowadays a long wide street, the

Via della Conciliazione, built by Mussolini after the conclusion of the

Lateran Treaties, leads from the River Tiber to the piazza and gives distant views of St. Peter's as the visitor approaches.

[15]

Bernini's transformation of the site is entirely Baroque in concept. Where Bramante and Michelangelo conceived a building that stood in "self-sufficient isolation", Bernini made the whole complex "expansively relate to its environment".

[31] Banister Fletcher says "No other city has afforded such a wide-swept approach to its cathedral church, no other architect could have conceived a design of greater nobility...(it is) the greatest of all atriums before the greatest of all churches of Christendom."

[6]

[edit]Treasures

Air vents for the crypt in St. Peter's Basilica

[edit]Tombs and relics

There are over 100 tombs within St. Peter's Basilica (extant to various extents), many located in the

Vatican grotto, beneath the Basilica. These include 91 popes, St.

Ignatius of Antioch, Holy Roman Emperor

Otto II, and the composer

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina. Exiled Catholic British royalty

James Francis Edward Stuart and his two sons,

Charles Edward Stuart and

Henry Benedict Stuart, Cardinal Bishop of Frascati, are buried here, having been granted asylum by

Pope Clement XI. Also buried here are

Maria Clementina Sobieska, wife of James Francis Edward Stuart, Queen

Christina of Sweden, who abdicated her throne in order to convert to Catholicism, and Countess

Matilda of Tuscany, supporter of the Papacy during the

Investiture Controversy. The most recent interment was

Pope John Paul II, on 8 April 2005. Beneath, near the

crypt, is the recently discovered vaulted fourth-century "

Tomb of the Julii". (See below for some descriptions of tombs)

[edit]Artworks

[edit]The towers and narthex

- In the towers to either side of the facade are two clocks. The clock on the left has been operated electrically since 1931. Its oldest bell dates from 1288.

- One of the most important treasures of the basilica is a mosaic set above the central external door. Called the "Navicella", it is based on a design by Giotto (early 14th century) and represents a ship symbolising the Christian Church.[7] The mosaic is mostly a 17th century copy of Giotto's original.

- At each end of the narthex is an equestrian figure, to the north Emperor Constantine by Bernini (1670) and to the south Charlemagne by Cornacchini (18th century).[7]

- Of the five portals from the narthex to the interior, three contain notable doors. The central portal has the Renaissance bronze door by Antonio Averulino (called Filarete) (1455), enlarged to fit the new space. The southern door, the "Door of the Dead", was designed by 20th century sculptor Giacomo Manzù and includes a portrait of Pope John XXIII kneeling before the crucified figure of St. Peter.

- The northernmost door is the "Holy Door" which, by tradition, is walled-up with bricks, and opened only for holy years such as the Jubilee year by the Pope. The present door is bronze and was designed by Vico Consorti in 1950. Above it are inscriptions commemorating the opening of the door: PAVLVS V PONT MAX ANNO XIII and GREGORIVS XIII PONT MAX. Recent commemorative plaques read:

PAVLVS VI PONT MAX HVIVS PATRIARCALIS VATICANAE BASILICAE PORTAM SANCTAM APERVIT ET CLAVSIT ANNO IVBILAEI MCMLXXV

Paul VI, Pontifex Maximus, opened and closed the holy door of this patriarchal Vatican basilica in the jubilee year of 1975.

IOANNES PAVLVS II P.M. PORTAM SANCTAM ANNO IVBILAEI MCMLXXVI A PAVLO PP VI RESERVATAM ET CLAVSAM APERVIT ET CLAVSIT ANNO IVB HVMANE REDEMP MCMLXXXIII – MCMLXXXIV

John Paul II, Pontifex Maximus, opened and closed again the holy door closed and set apart by Paul VI in 1976 in the jubilee year of human redemption 1983-4.

IOANNES PAVLVS II P.M. ITERVM PORTAM SANCTAM APERVIT ET CLAVSIT ANNO MAGNI IVBILAEI AB INCARNATIONE DOMINI MM-MMI

John Paul II, Pontifex Maximus, again opened and closed the holy door in the year of the great jubilee, from the incarnation of the Lord 2000–2001.

[edit]The nave

- On the first piers of the nave are two Holy Water basins held by pairs of cherubs each 2 metres high, commissioned by Pope Benedict XIII from designer Agostino Cornacchiniand sculptor Francesco Moderati, (1720s).

- Along the floor of the nave are markers showing the comparative lengths of other churches, starting from the entrance.

- On the decorative pilasters of the piers of the nave are medallions with relief depicting the first 38 popes.

- In niches between the pilasters of the nave are statues depicting 39 founders of religious orders.

- Set against the north east pier of the dome is a statue of St. Peter Enthroned, sometimes attributed to late 13th century sculptor Arnolfo di Cambio, with some scholars dating it to the 5th century. One foot of the statue is largely worn away by pilgrims kissing it for centuries.

- The sunken Confessio leading to the Vatican Grottoes (see above) contains a large kneeling statue by Canova of Pope Pius VI, who was captured and mistreated by Napoleon's army.

- In the Confessio is the Niche of the Pallium ("Niche of Stoles") which contains a bronze urn, donated by Pope Benedict XIV, to contain white stoles embroidered with black crosses and woven with the wool of lambs blessed on St. Agnes' day.

- The High Altar is surmounted by Bernini's baldachin. (See above)

- Set in niches within the four piers supporting the dome are the statues associated with the basilica's holy relics: St. Helena holding the True Cross, by Andrea Bolgi; St. Longinus holding the spear that pierced the side of Jesus, by Bernini (1639); St. Andrew with the St. Andrew's Cross, by Francois Duquesnoy and St. Veronica holding her veil with the image of Jesus' face, by Francesco Mochi.

Statues in the piers of the dome

[edit]North aisle

- In the first chapel of the north aisle is Michelangelo's Pietà.[43]

- On the first pier in the right aisle is the monument of Queen Christina of Sweden, who abdicated in 1654 in order to convert to Catholicism.

- The second chapel, dedicated to St. Sebastian, contains the statues of popes Pius XI and Pius XII. The space below the altar used to be the resting place of Pope Innocent XIbut his remains were moved to the Altar of the Transfiguration on 8 April 2011. This was done to make way for the body of Pope John Paul II. His remains were placed beneath the altar on 2 May 2011.

- The large chapel on the right aisle is the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament which contains the tabernacle by Bernini (1664) resembling Bramante's Tempietto at San Pietro in Montorio supported by two kneeling angels and with behind it a painting of the Holy Trinity by Pietro da Cortona.

- Near the altar of Our Lady of Succour are the monuments of popes Gregory XIII by Camillo Rusconi (1723) and Gregory XIV.

- At the end of the aisle is an altar containing the relics of St. Petronilla and with an altarpiece "The Burial of St Petronilla by Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri), 1623.

[edit]South aisle

- The first chapel in the south aisle is the baptistry, commissioned by Pope Innocent XII and designed by Carlo Fontana, (great nephew of Domenico Fontana). The font, which was previously located in the opposite chapel, is the red porphyry sarcophagus of Probus, the 4th century Prefect of Rome. The lid came from a different sarcophagus, which had once held the remains of the Emperor Hadrian and in removing it from the Vatican Grotto where it had been stored, the workmen broke it into ten pieces. Fontana restored it expertly and surmounted it with a gilt-bronze figure of the "Lamb of God".

- Against the first pier of the aisle is the Monument to the Royal Stuarts, James and his sons, Charles Edward, known as "Bonnie Prince Charlie" and Henry, Cardinal and Duke of York. The tomb is a Neo-Classical design by Canova unveiled in 1819. Opposite it is the memorial of James Francis Edward Stuart's wife, Maria Clementina Sobieska.

- The second chapel is that of the Presentation of the Virgin and contains the tombs of Pope Benedict XV and Pope John XXIII.

- Against the piers are the tombs of Pope Pius X and Pope Innocent VIII.

- The large chapel off the south aisle is the Choir Chapel which contains the altar of the Immaculate Conception.

- At the entrance to the Sacristy is the tomb of Pope Pius VIII

- The south transept contains the altars of St. Thomas, St. Joseph and the Crucifixion of St. Peter.

- The tomb of Fabio Chigi, Pope Alexander VII, towards the end of the aisle, is the work of Bernini and called by Lees-Milne "one of the greatest tombs of the Baroque Age". It occupies an awkward position, being set in a niche above a doorway into a small vestry, but Bernini has utilised the doorway in a symbolic manner. Pope Alexander kneels upon his tomb, facing outward. The tomb is supported on a large draped shroud in patterned red marble, and is supported by four female figures, of whom only the two at the front are fully visible. They represent Charity and Truth. The foot of Truth rests upon a globe of the world, her toe being pierced symbolically by the thorn of Protestant England. Coming forth, seemingly, from the doorway as if it were the entrance to a tomb, is the skeletal winged figure of Death, its head hidden beneath the shroud, but its right hand carrying an hourglass stretched upward towards the kneeling figure of the pope.[15]

The Holy Door is opened only for great celebrations.

The Pietà by Michelangelo is in the north aisle

Truth, by

Bernini. Her big toe is pierced by a thorn from Britain.

[44]

[edit]Archpriests since 1053

Cardinals at

Mass in Saint Peter's Basilica two days before a

papal conclave, 16 April 2005.

[edit]Specifications

- Cost of construction of the basilica: 46,800,052 ducats[46]

- Geographic orientation: chancel west, nave east

- Capacity: 60,000 +[citation needed]

- Total length: 730 feet (220 m)

- Total width: 500 feet (150 m)

- Interior length including vestibule: 693.8 feet (211.5 m),[4] more than 1/8 mile.

- Length of the transepts in interior: 451 feet (137 m)[4]

- Width of nave: 90.2 feet (27.5 m)[4]

- Width at the tribune: 78.7 feet (24.0 m)[4]

- Internal width at transepts: 451 feet (137 m)[4]

- Internal height of nave: 151.5 feet (46.2 m) high[4]

- Total area: 227,070 square feet (21,095 m2), more than 5 acres (20,000 m2).

- Internal area: 163,182.2 square feet (3.75 acres; 15,160.12 m2)[4]

- Height from pavement to top of cross: 452 feet (138 m)

- Façade: 167 feet (51 m) high by 375 feet (114 m) wide

- Vestibule: 232.9 feet (71.0 m) feet wide, 44.2 feet (13.5 m) deep, and 91.8 feet (28.0 m) high[4]

- The internal columns and pilasters: 92 feet (28 m) tall

- The circumference of the central piers: 240 feet (73 m)

- Outer diameter of dome: 137.7 feet (42.0 m)[4]

- The drum of the dome: 630 feet (190 m) in circumference and 65.6 feet (20.0 m) high, rising to 240 feet (73 m) from the ground

- The lantern: 63 feet (19 m) high

- The ball and cross: 8 and 16 feet (2.4 and 4.9 m), respectively

- St. Peter's Square: 1,115 feet (340 m) long, 787.3 feet (240.0 m) wide[4]

- Each arm of the colonnade: 306 feet (93 m) long, and 64 feet (20 m) high

- The colonnades have 248 columns, 88 pilasters, and 140 statues[4]

- Obelisk: 83.6 feet (25.5 m). Total height with base and cross, 132 feet (40 m).

- Weight of obelisk: 360.2 short tons (326,800 kg; 720,400 lb)[4]

- ^ a b Banister Fletcher, the renowned architectural historian calls it "the greatest creation of the Renaissance" and "...the greatest of all churches of Christendom" in Fletcher 1996, p. 719.[clarification needed]

- ^ a b Claims made that the Basilica of Our Lady of Peace of Yamoussoukro in Côte d'Ivoire is larger appear to be spurious, as the measurements include a rectorate, a villa and probably the forecourt. Its dome, based on that of St. Peter's, is lower but carries a taller cross, and thus claims to be the tallest domed church.

- ^ James Lees-Milne describes Saint Peter's Basilica as "a church with a unique position in the Christian world" in Lees-Milne 1967, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Baumgarten 1913

- ^ Papal Mass (accessed 28-02-2012)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fletcher 1975

- ^ a b c d e Pio V. Pinto, pp. 48–59

- ^ "St. Peter's Square – Statue of St. Paul". Saintpetersbasilica.org. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ Georgina Masson, The Companion Guide to Rome, (2003), pp. 615–6

- ^ Helen F. North, quoted in Secrets of Rome, Robert Kahn, (1999) pp. 79–80

- ^ Ralph Waldo Emerson, 7 April 1833

- ^ Benedict XVI’s theological act of renouncing the title of "Patriarch of the West" had as consequence that Roman Catholic patriarchal basilicas are today officially known asPapal basilicas.

- ^ "St. Peter's Basilica — Interior of the Basilica". Internet Portal of the Vatican City State. p. 2. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: St. Peter, Prince of the Apostles". New Advent. 1 February 1911. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Lees-Milne 1967

- ^ Frank J. Korn, Hidden Rome Paulist Press (2002)

- ^ Hijmans, Steven. "University of Alberta Express News". In search of St. Peter's Tomb. Retrieved 25 December 2006.

- ^ Cunningham, Lawrence (2010), Cultures and Values, USA: Clark Baxter, pp. 671

- ^ Dietz, Helen (2005), "The Eschatological Dimension of Church Architecture",Sacred Architecture Journal 10

- ^ Boorsch, Suzanne (Winter 1982–1983), "The Building of the Vatican: The Papacy and Architecture", The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 40 (3): 4–8

- ^ Quarrying of stone for the Colosseum had, in turn, been paid for with treasure looted at the Siege of Jerusalem and destruction of the temple by the emperor Vespasian's general (and the future emperor) Titus in 70 AD., Claridge, Amanda (1998). Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide (First ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1998. pp. 276–282. ISBN 0-19-288003-9.

- ^ Julius II's tomb was left incomplete and was eventually erected in the Church of St Peter ad Vincola.

- ^ "Johann Tetzel", Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2007: "Tetzel's experiences as a preacher of indulgences, especially between 1503 and 1510, led to his appointment as general commissioner by Albrecht, archbishop of Mainz, who, deeply in debt to pay for a large accumulation of benefices, had to contribute a considerable sum toward the rebuilding of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. Albrecht obtained permission from Pope Leo X to conduct the sale of a special plenary indulgence (i.e., remission of the temporal punishment of sin), half of the proceeds of which Albrecht was to claim to pay the fees of his benefices. In effect, Tetzel became a salesman whose product was to cause a scandal in Germany that evolved into the greatest crisis (the Reformation) in the history of the Western church."

- ^ Hillerbrand, Hans J. "Martin Luther: Indulgences and salvation," Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2007.

- ^ a b Hartt 2006

- ^ Bramante's plan, Gardner, Kleiner & Mamiya 2005, p. 458

- ^ Raphael's plan, Fletcher 1996, p. 722[clarification needed]

- ^ Peruzzi's plan, Fletcher 1996, p. 722[clarification needed]

- ^ a b Sangallo's plan, Fletcher 1996, p. 722[clarification needed]

- ^ Goldscheider 1996

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gardner, Kleiner & Mamiya 2005

- ^ Michelangelo's plan, Gardner, Kleiner & Mamiya 2005, p. 458

- ^ a b c Eneide Mignacca, Michelangelo and the architecture of St. Peter's Basilica, lecture, Sydney University, (1982)

- ^ This claim has recently been made for Yamoussoukro Basilica, the dome of which, modelled on St. Peter's, is lower but has a taller cross

- ^ The dome of Florence Cathedral is depicted in a fresco at Santa Maria Novella that pre-dates its building by about 100 years.

- ^ *Galassi Alghisii Carpens., apud Alphonsum II. Ferrariae Ducem architecti, opus, by Galasso Alghisi, Dominicus Thebaldius (1563). page 44/147 of Google PDF download.

- ^ a b "Michelangelo 'last sketch' found". BBC News. 7 December 2007. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ^ BBC, Rare Michelangelo sketch for sale, Friday, 14 October 2005, [1] accessed: 9 February 2008

- ^ Another view of the façade statues. From left to right: ① Thaddeus, ② Matthew, ③ Philip, ④ Thomas, ⑤ James the Elder, ⑥ John the Baptist (technically a ‘precursor’ and not an apostle); ⑦ Christ (centre, the only one with a halo); ⑧ Andrew, ⑨ John the Apostle, ⑩ James the Younger, ⑪ Bartholomew, ⑫ Simon and ⑬ Matthias. ("Unofficial archietcture site". SaintPetersBasilica.org. Retrieved June 2011.)

- ^ The word "stupendous" is used by a number of writers trying to adequately describe the enormity of the interior. These include James Lees-Milne and Banister Fletcher.

- ^ Kilby, Peter. "St Peter's Basilica (Basilica di San Pietro)". Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ "St. Peter's, the Obelisk". Saintpetersbasilica.org. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ The statue was damaged in 1972 by Lazlo Toft, a Hungarian-Australian, who considered that the veneration shown to the statue was idolatrous. The damage was repaired and the statue subsequently placed behind glass.

- ^ St Peter's Basilica, The Seminarian GuidesNorth American College, Rome. Retrieved 29 July 2009.